Cinematographer Claudia Raschke Trips the Light Fantastic

Claudia Raschke, ASC grew up as a dancer in Germany before pursuing a remarkable career in cinematography. Images c/o Raschke.

When Claudia Raschke moved to New York in the ’80s, the plan was to pursue dance and find love (against her mother’s better judgment). She did even better. About a year after her move, while sitting at a restaurant downtown sifting through photographs to send home to her family in Germany, the bartender interrupted Raschke to ask if she’d ever thought about cinematography. She’d never heard of it.

Of course, cinematography soon became her world. Raschke has now shot several Oscar-nominated and Emmy-winning films, including RBG, Julia, Fauci, My Name Is Pauli Murray, and the recent Kevin Costner series The West, to name a few. Canon USA chose her to be the first among six cinematographers to be part of the Explorer of Light program in 2023. Just last week, she was officially welcomed into the prestigious American Society of Cinematographers (ASC).

In her remarkable 30-year-plus career that unfolded after that night, Raschke has traveled the world capturing moments and stories that might otherwise have never seen the light of day, including families in Nigeria fighting for clean water; the activists behind the marriage-equality movement; and the African-American woman on a bus who refused to give up her seat—15 years before Rosa Parks.

And she’s still got her foot on the gas.

Here at this pinnacle, Raschke shares what it took to break into the male-dominated industry and make her mark, including the first time she discovered a Super 8 camera, how she uses cinematography to continue dancing, and why she believes you should never let the door close behind you on your way out.

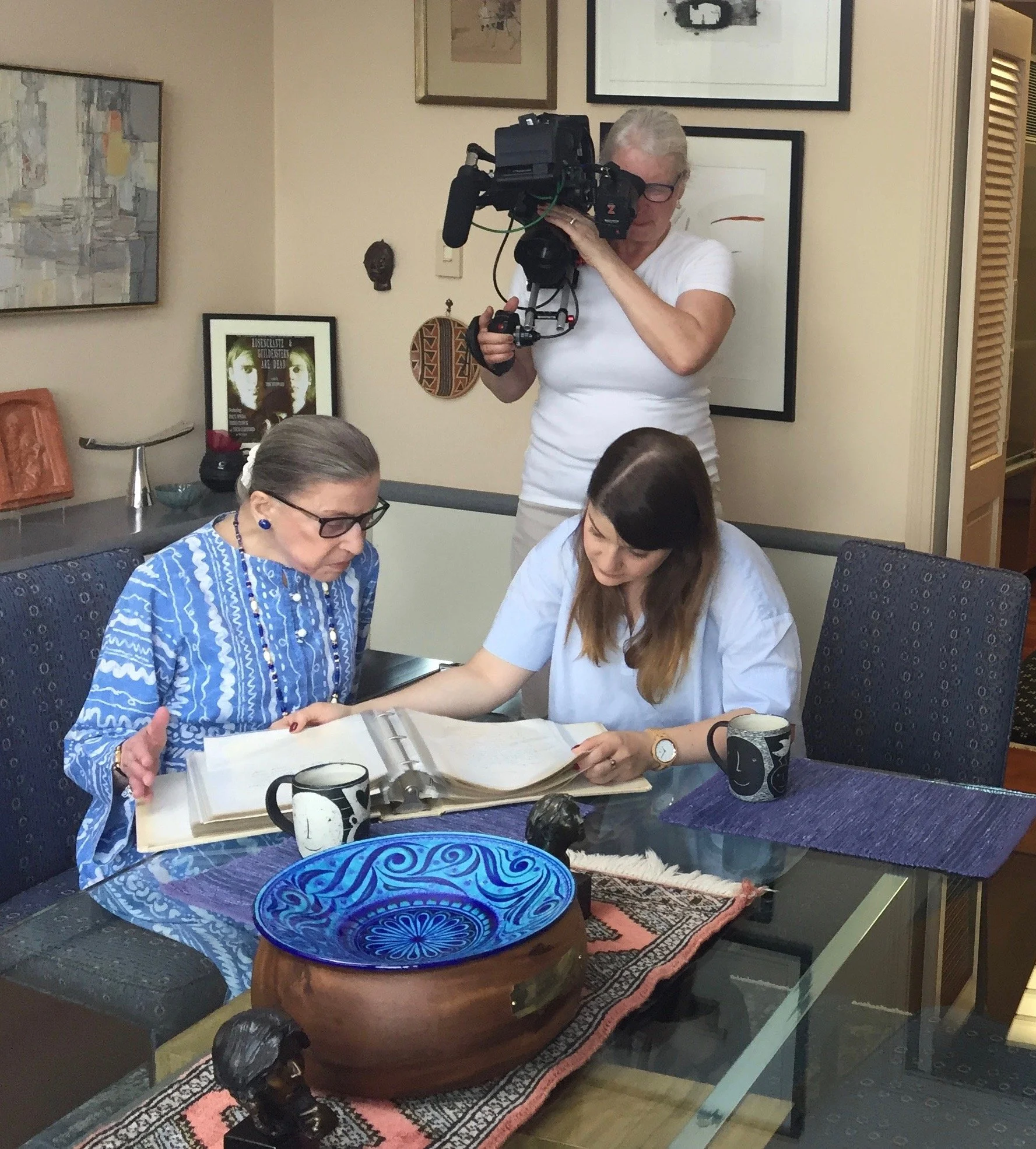

When shooting RBG, Rachke had to work fast. Ginsburg only allowed the team 20-minutes at a time to shoot.

On set in Africa, where Raschke’s job was to tell the story about Nigeria’s push for clean water.

You moved to NYC with the intent of becoming a dancer. What type of career did you envision for yourself, and how did you break into the world of cinematography?

When I came to New York in the mid-’80s, I studied at the Martha Graham School of Dance, which is how I was allowed to be in America, but I was taking photographs to send back home to my family. One day, I showed my work to a bartender at a restaurant, who was also a part-time film professor at Columbia University, and he seemed to think that I had a good eye. He asked if I’d ever thought about cinematography. I said, What the heck is cinematography?

The professor invited me to a student film set to help with the camerawork. The minute I was on set, it was an awakening. It’s as if I was blind to something, and somebody said, Hey, look out of this window over here to the left, and suddenly I could see this whole view I’d never seen before. So there I was on the set, and everybody was hustling, carrying stands and lights, and mocking things up on the floor. People were shuffling around; it was hectic and chaotic. And then the director said, Okay, all right, are we ready to roll? Okay? And then the clapper would announce the take, and the camera would start rolling, and everyone else became invisible. They became shadow figures—completely quiet, not making a sound—and it was as if we were at this threshold, or this magical dividing line between reality and fantasy. When the director called action, the actors transformed the scripted scene into a new reality.

I saw all the art forms unfold before my eyes: I could paint using light and shadows; I could sculpt a spatial experience with the lenses for the camera; I could dance and choreograph using camera movements in conjunction with the actors. All of this was something that I had trained for, and it was all coming together in such a beautiful way. It was like fireworks in my head—this is what I need to do the rest of my life.

Raschke still considers herself a dancer; dancing with her camera.

It seems there’s a common thread among the subjects of your works: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Julia Child, Pauli Murray, and Anthony Fauci. Is it a coincidence that you’ve worked on so many films that cover social justice themes, or do you gravitate toward them for a reason?

I gravitate toward films surrounding a social issue, whether that’s defending rights or highlighting the stories of those who have been discriminated against. I suspect it has a lot to do with the history of where I grew up. You know, growing up in a country that was completely taken over by Hitler, one that was so brutal and gruesome, it becomes this lifelong thread. When I see injustice that I do not understand, I search for ways to understand it. And so I embrace films that handle it and pull the curtain away.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s story spans decades of history and impact. What was the toughest part of shaping that into a documentary?

I would say, the hardest part was having very limited access and time with RBG. Her work schedule was crazy busy. Plus, there were strict rules we had to follow to even get into the Supreme Court building. Everything had to be approved by multiple entities. Once we had access, we were given a 20-minute slot to film her. So absolutely everything had to be prepped prior. The directors, Julie Cohen and Betsy West, were nervous. 20 minutes doesn’t allow for any mistakes. Especially not any “Oops, my camera has a tech problem,” or “I need to adjust the light for her.” The pressure was on once the time was ticking. My mind kept racing to make sure I would capture the perfect moment in the most powerful way to show how amazing she was. Thankfully, once RBG trusted us, we were granted more 20-minute slots. Still, each time, the pressure and anxiety of potentially messing up were huge.

How do you tell a story about someone who is no longer with us, like with Julia?

The art is to create a visually and emotionally compelling bridge the viewer can walk on and over into the heart of the story. In Julia, I chose to bring in the point of view of a child standing right next to her whipping up her delicious recipes. I wanted the camera perspective to be at eye-level of the table and very close to the cook’s hands preparing the food. I mean, so close that you could smell it or feel propelled to stick your finger into the pie. This view creates a joint experience with the viewer to witness the magic and trigger their own memories of watching their mom or dad bake a cake or the most favorite family food we all cherish so much. It’s most important to let someone’s life story grab you in an emotional way so you can relate, no matter if they have passed or are still alive.

When you set out to film Fauci, it was during a global pandemic, of course. How did you navigate the constraints?

COVID was in full swing, and every day was filled with tests and masks. Getting into the NIH building complex is like getting into Fort Knox with security, badges, and car searches to the tenth degree. Once we passed the scrutiny, we had clear access. However, everything was planned out carefully.

His interview was a challenge. Nobody would ever know the lengthy effort we went through to set up and work around his larger-than-life potted plant in his office. Fauci’s interview had to look like one continuous event. We shot it in six different sittings, each lasting about four to five hours. Each time, I had to match all my lighting levels and positions, camera set-ups, background props, position of the chair to the background. I had never done this kind of precision work for a documentary before. The prep alone was three hours long, and after the interview, everything had to be reset to normal.

Raschke always pursues films that tell an important story. She can’t not.

It’s rare for women to break into the world of cinematography. What has your experience in the industry been like?

The first time I truly noticed the role of my gender in the industry was on a location scout for a film. I remember I was walking with the director, and I pointed out that there were telephone wires everywhere, which was not going to work for our period film. And he said, Okay, let’s look over there and he walked off. Eventually, the assistant director caught up to me and asked me for my thoughts, and I told him the same thing—that I was really concerned about all the telephone wires. So the assistant director took his megaphone and announced to everyone that the location wouldn’t work and we should leave. And right then and there, the director walked up to me and asked me why I hadn’t said anything to him. Of course, I was speechless. To him, I was white noise—he literally did not hear me. When you’re hired as an expert but you’re not listened to, it is often about something else. In my experience, it was about gender.

What’s one of the biggest obstacles or challenges you’ve overcome in your work?

The biggest challenge for me was to get a foot in the door. During the ’80s, when I entered the industry, there was this whole stigma that women couldn’t handle the stress of the work, or technical complexities, or even the weight of the equipment. The reality for so long was that I was the only woman on set. And so I carried an incredible weight on my shoulders; like if I make a mistake, it might close the door for many women to follow. I’d walk on set being painfully aware that people would greet me with doubt, looking for my weakness. And I prepared like a maniac. I knew the script better than the director, and I found a way to be a diplomat without coming on too strong.

It’s still bad today. Only about 8 percent of cinematographers are women. The only way forward was to band together with other women. Don’t just walk through the door and let it shut behind you.

How did you navigate it?

When I first entered the industry, I didn’t think twice about the fact that I might face this obstacle. My mother was a very outspoken businesswoman, and I knew I would be too. My passion for cinematography was so all-consuming that there was no other choice. And because I was European, I was also somewhat exotic in the industry. My identity helped me maneuver around because I could be playful with the rules. I could say things like, Oh, we don’t do things that way in Europe. It was like a diplomacy of deflection; a way of not taking anything like it was written in stone.

What led you to pursue art in the first place?

My parents, inevitably. I grew up in the northern part of Germany in the city of Hamburg, a merchant town. It has more bridges than Venice does, and there’s a lot of trade. I felt my life was very secure; my parents both worked, and they told stories, sometimes disciplined me and my two siblings, and occasionally we indulged in traveling. The house was always full of music and media. My mother worked in movie theaters, and the essence of my childhood was watching James Bond films and comedies with Laurel and Hardy. It was important to my parents that we have conversations and reflect on what we read and saw. They would gather us around the dinner table and read us a story, and then, after dinner, we would talk about it. My father was a writer and teacher, so we were often reading silly poems or debating with each other on a number of subjects.

When did you discover your first camera?

I was very little, and my dad brought home a Super 8 camera and showed me some in-camera tricks, like rolling the footage, then stopping it, and rolling it again with a new shot. So there was that in-between time, when something happened in real life when we weren’t filming, and then the camera picked up somewhere new. So it kind of accelerated time, like magic. And I guess that really influenced me in terms of looking at films differently, because I understood there was magic that was happening in the camera.

Raschke on set for Obsessed with Light (2023), a documentary about American performer Loie Fuller.

“I had to learn and accept that I was affected by the process, because I couldn’t just observe and follow.”

Looking back over the course of your career, can you remember the best day you’ve had on set? Can you describe it to me?

Actually, it was recently on set for a feature documentary, which will premiere in 2026 called MAKE WORK. It is about the New York City Ballet’s focus on new choreography. And as you know, I was a dancer, and I still consider myself a dancer. This particular documentary mostly took place in the rehearsal room with choreographers and excellent dancers who executed their brand-new movement ideas. You never knew what might happen, or what kind of movement rays would come of it, and how that would explode into an emotion. And so, how do I cover that?

When I shoot documentaries, I shoot 360 degrees, so the directors, Linda Saffire and Adam Schlessinger, had to hide in the next room while my sound man and I worked hand-in-hand avoiding the large dance mirrors being totally focused on our ballet dancers. But this was different. If I move independently from them, we might collide, and that’s going to be a problem.

So after the first day, I went home, and I have this little mind map book. It’s basically a journal where every time I do a film, I write down my experience and describe how my mind was ignited. Instead of just looking at the dancers as single entities, I wrote about them as the ebb and flow of energies coming together. My choice was either that the camera moves and matches their energy, which means I needed to know the choreography to harmonize with them—being linked and in their personal space, or I could be still while they moved, or vice versa, like a give and take. I had to learn and accept that I was affected by the process, because I couldn’t just observe and follow. I came to the conclusion that I could be a source for the dancers to play off of. Over time, they started trusting me. They knew that I would jump out of their way at the last moment, or that I would rotate out of the way and spin with their energy into a new direction. It inspired entirely new camera choreography, in a way. And it gave me a feeling of liberty that I had not experienced in so long; a liberty with my camera movement.

Build Your Creative Braintrust — Join Creative Factory

Join more than 50 leaders from top organizations, including Amazon, Spotify, Disney, Stripe, Shake Shack, NASA, Cannondale, Roblox, Hearst, Clay, Paramount, and more.