How Songwriter and Producer Sam Hollander Played the Long Game and Struck Chart Gold

Sam Hollander has had 23 top hits and over 14 billion streams — and he’s still just getting started. Images c/o Hollander.

You’ve probably already memorized some of Sam Hollander’s work. “Had to have high, high hopes for a living” ring any bells?

Sam Hollander is a professional songwriter and producer. Working with everyone from Panic! At the Disco, Katy Perry, and Carole King to Billy Idol, Def Leppard, and Wheezer, Hollander has had 23 U.S. Top 40 hits and 111 Top 10 chart positions globally. His catalog totals over 14 billion streams and includes multiplatinum hits not limited to “High Hopes” and “Hey Look Ma, I Made It!” (Panic! At The Disco), “HandClap” (Fitz and the Tantrums), and “Rock Me” (OneDirection). He has been Rolling Stone’s Hot List Producer of the Year, served as the Governor of the GRAMMYs New York Chapter, and even earned an Emmy nomination for work in SMASH.

I first met Hollander around four years ago. He is incredibly down to Earth for the number of insane contacts that live in his back pocket, and last week, he agreed to sit down with me at our local town pizza place.

Here, Hollander shares the details behind how he works, including breaking into the industry; his creative process; and his thoughts on songwriting in today's world.

Hollander’s secret is that he never waits for the phone to ring — his foot is always on the gas.

Can you tell me about your path into the music industry? What were some pivotal moments and what did you learn from them that helped you reach this point in your career?

My path was akin to a slow car wreck. I decided that I’d be a songwriter at 14 and despite barely being able to play four chords on guitar, I still told everyone I’d make it. I had ADHD before anyone diagnosed it, bottom of my class, and the first college dropout in my year (I made it 18 hours, quite the distinction). I attended 3 universities in 2 semesters. Still, I had this vision that I’d write songs for a living. I wrote poetry, I was very lyrical, and I felt like I had an interesting voice so I thought I could will it into reality.

With no clear entry point or instruction manual, I discovered hip hop in the late ’80s. I tried to cast other people to rap for me, but they all passed so I figured, Okay. I’m going to be the rapper. And I did it. And that was terrible. Still, at 20, I got a record deal and dropped out of NYU. That was the beginning.

Then you got your first #1 hit with “Cupid’s Chokehold” followed close by “The Great Escape” with Boys Like Girls.

Yeah. It was surreal. “Cupid’s Chokehold” was my first hit and my first #1 hit and at the exact same time, I had put together Boys Like Girls and released “The Great Escape.” When “Cupid’s Chokehold” hit #1, “The Great Escape” was #7 or #8. I went from zero success to two songs in the Top 10. I’ve always believed in the notion that anyone is capable of having a hit and that was the moment when I realized If I can do two, I’m gonna have 100.

I had written 10,000 sounds and spent years chasing trends but I started to finally understand why songs worked musically, and all of my influences that were inherently uncool suddenly became cool. Sometimes it’s a game of attrition. You stick it out and hope the universe meets you halfway and that’s what happened.

Looking at your story, you consistently worked hard to create your own opportunities. You lobbied hard for Brendan Yuri to let you work on the verses of “High Hopes.” It seems like doing that work was an essential part of building your career.

The misnomer in this business is when you have a morsel of success, that brings you work. The phone rings, but that complacency is never gonna work. I also entered the business with a chip on my shoulder because I was the kid nobody believed would do this. So, I knew that I could never take my foot off the gas.

Even now, I am still hitting people directly. I see a composite painting of my work in my head where I can position every one of the artists I’ve worked with. Ringo is here, Train is here, and Weezer is here. If I feel like there’s a hole in that painting that I want to fill and there’s an artist who would qualify for it, then I’m gonna go for it. Artists like to hear from artists and the best work and the best relationships are born out of reaching out directly.

How do you divide your time between actually doing the creative work versus reaching out to artists?

Three quarters creativity and figuring out the music, one quarter cleaning up shop and making rounds via phone, web, or in-person. You’d be surprised — there are things that we have to do that on paper seem so mundane and should be so easy but, because we’re creatives, we can barely shower. Just the notion of me having to sign a DocuSign for a split sheet, it’s very overwhelming for a guy like me.

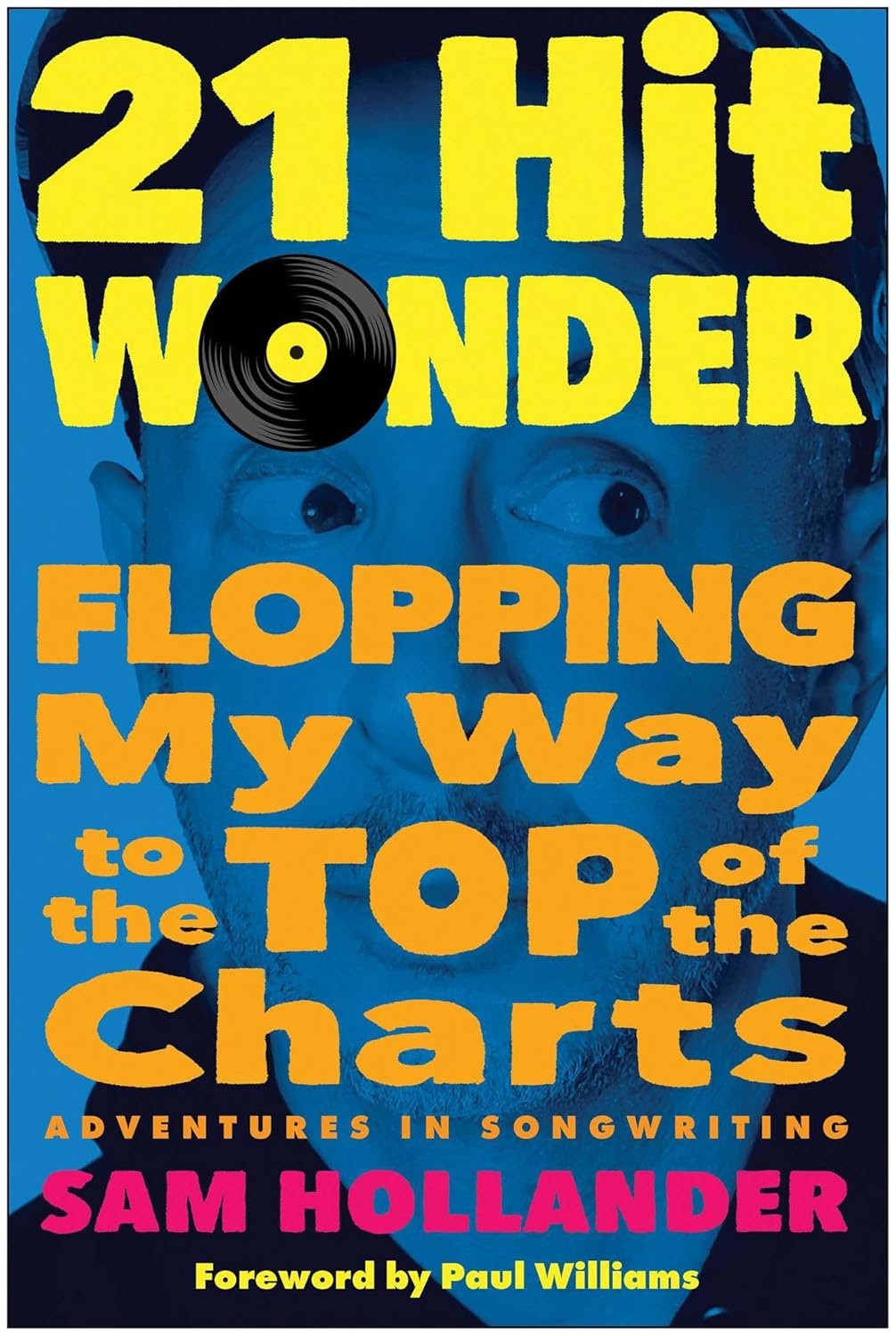

21 Hit Wonder: Flopping My Way to the Top of the Charts shares exercises that elevated specific elements of craft (crafting melodies over just two chords), ingenious career-launching maneuvers (turning your studio’s voicemail into a personal promo), and stories of devouring biographies of idols, mass cold emailing, and sheer perseverance (and also being babysat by Andy Warhol).

What is your creative process?

I write in so many different genres that a good portion of my time is re-farmiliarizing myself to make sure what I’m writing feels authentic. When I made the OJS farewell record, I had to come in and figure out how to write 70s soul of a specific time. It was very chordal and melodic and that’s so outside of my box. So, I study, listen, and break it down until I figure out the puzzle and I play with AI like crazy.

What’s your perspective on the rise of generative music composition AI models (Suno, Udio) and how do you use them in your work?

I’m a big AI guy. With Suno, I can pull up any song I’ve written since the ’90s that never got recorded, drop it in, and in seven seconds have a modern demo in any genre. I wouldn’t rely on it for lyrics because there’s still a human element missing, but it inspires great ideas. Maybe it spits out a garbage verse, but one great couplet that I’ll keep. To me, it’s just another co-writer.

I spend at least 30 minutes a day just playing with AI to understand how it can also be useful for samples. I can ask for a ’70s jazz fusion horn section and it’ll give me something I can sample to make a hip hop track. It’s the greatest creative revelation I’ve experienced.

AI also broadens collaboration. It opens your mind to hearing music differently. If I run a song demo through AI and massage the prompts to play with the backdropping, maybe it puts a gospel tinge on the piano that I never would have thought of. Then bring in a real gospel player for the final record.

There’s still skepticism in the industry. I think there’s a Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy right now. But the truth is, if you don’t embrace it, you’ll be left behind. That said, I also love the idea of a whole counter reaction organic movement; musicians in the woods in Vermont will be playing in the woods with acoustic guitars and kumbaya. There’s space for both. Personally, I see AI as a tool for curiosity and for expansion. Two years ago with Public Enemy, Flavor wanted his song rapped in 25 different languages. We were the first people to build a Flavor model and worked with rappers around the world to re-record the song in their native language and then load that into Flavor’s voice. Now on Spotify, there’s 25 versions of that song with his voice.

Some people call that cheating. I think it’s amazing.

How do you manage balancing the ideas and opinions of so many different creatives (producers, artists, other writers, etc.) when you’re coming into a project with a role that isn’t clearly defined?

My job is always to support the artists, but I’m also not going to let the train derail.

It’s incredibly important that I’ve prepped before I’ve gotten in a room with anybody. I do more due diligence than most writers I know. If I feel very strongly about it, I’m going to fight for it respectfully. And if I miss, I miss and at least I tried. I’m totally cool with it but I don’t have a passive approach.

You’ve mentioned before that a lot of your first dives into songwriting found inspiration through ’80s-high-school-movie binges. Is that still where you turn for inspiration now?

I have other sources. I watch a ton of documentaries and YouTube has become my de facto ’80s movie. I’m on it 24 hours a day. And I love YouTube because the algorithm suits me and it goes to very strange places.

But, the greatest skill you can ever have is to be a listener. I find inspiration in everything and I spend a lot of my time eavesdropping. The universe sends you signals and I can hear somebody’s conversation and instantly say, That’s a title or That’s a concept, you know? It’s just really about staying awake.

You wrote your book, 21-Hit Wonder: Flopping My Way to the Top of the Charts, with no ghost or co-writers. How did the creative process of writing a book solo compare to your collaborative songwriting process?

I wouldn’t let anyone touch my book exactly because of my life as a creative collaborator. This is the moment where I had to record my entire journey and really do all the heavy lifting all by myself so it could feel like my tone and feel like actually somebody who is a little off the rails. And it was, hands down, the most satisfying thing I’ve ever done.

Books in this genre tend to read like humble brags; 10 pages of struggle then 250 pages of success but that’s not the industry. That’s why I end my book with getting fired by Jimmy Fallon. I’m still getting fired at the age of 50. I think a lot of people are delusional and believe, Wow. The second I ascertain something, I’m on and it just cruises on like Tom Cruise forever. You’re not and Tom Cruise has had bad days. You have to keep working at it.

In today’s new landscape, how does the path into the industry compare to when you were starting out? What would you tell a younger version of yourself if you were starting out right now?

The entertainment industry of 2025 has nothing to do with the one that I came up in. My book is basically irrelevant now because it doesn’t discuss AI. I came up in an age when radio was king, 1959 through 2020. Now, radio is a microcosm of what it was. We used to have a defined path of writing a song, working with any artist, hoping they would get a record deal, getting the radio department to spend a lot of money to get it played, and then maybe people would call into their radio stations and suddenly you had a hit and sales would increase. It was the most freakish, magical perfect storm to witness. That doesn’t really happen anymore. Now, a 20 year old kid from NYC can blow up and become the biggest artist on Spotify out of nowhere. Anybody can do it. It’s great.

The gatekeepers are gone so it’s a very exciting time to be a creative because, truthfully, you can permeate anything in 2025. The flip side is you have more competition than ever before. In the Brill Building of the early 1960s, you had like 10 writers from Brooklyn who all became the biggest songwriters in the world because it was such a young business and the pool was so small. Now, there are probably 10 people right now writing songs into AI as we speak and uploading. You’re competing with what, a million songs getting uploaded every day? Creativity still matters and if you have the heart or talent, it is the same idea. The game’s just played very differently now. So, if I were starting now, my advice would be to spend copious amounts of time keeping up with tech. Following where the tech is going and that’s where the future of this industry lives.

Build Your Creative Braintrust — Join Creative Factory

Join more than 30 leaders from top organizations, including Spotify, Disney, Stripe, Shake Shack, Target, NASA, Cannondale, Roblox, Hearst, Clay, Paramount, and The Aspen Institute.