Good Splits: Peace, Love and Royalties

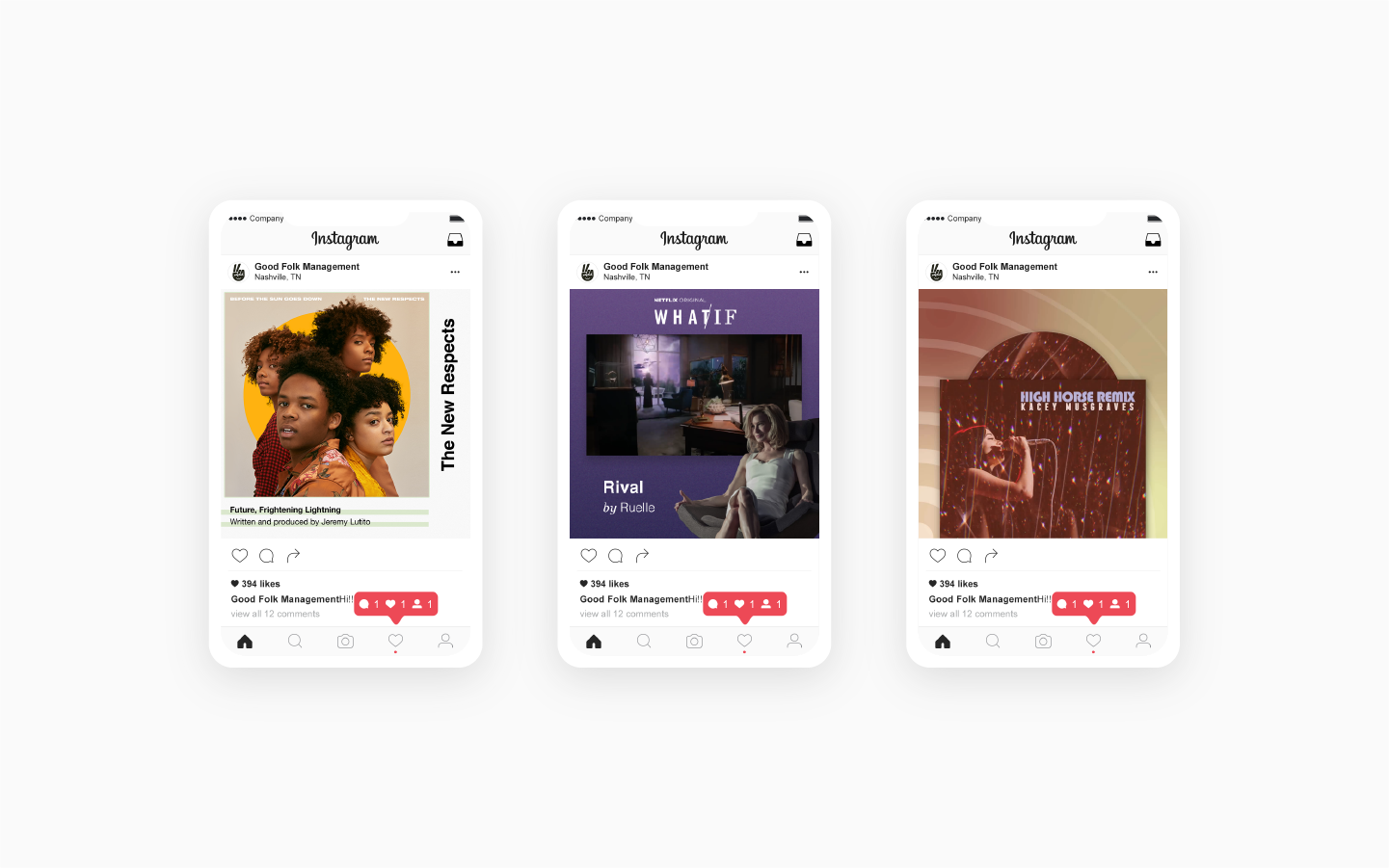

Jordan Mattison, song royalty calculator folk hero. Images courtesy of Good Splits.

Busywork is the bane of a creator’s existence. So Jordan Mattison created “Good Splits” to remove a major royalty accounting headache for musicians who can now spend more time on songs.

To his internship interview, Jordan Mattison wore the boxy, black J.C. Penney suit his grandmother bought him to wear to her funeral. This was 2005; Mattison’s grandmother is still alive. “She's been planning on dying for like 50 years,” he says. That day the plucky 22-year-old Mississippi native broke into the music industry and landed a role at Nashville management agency Teleprompt. “I don't know if they were just embarrassed for me,” he says.

Mattison has always loved music. In the days before YouTube, he tried to record music directly from the TV. During the Video Music Awards one year, he set his boombox on a chair in front of the screen and hooked his headphones up to the boombox’s microphone jack. Spoiler alert: His first attempt at piracy failed.

At Teleprompt, Mattison worked as the merch manager to Mutemath, a New Orleans alt rock group. Soon, Mattison toured across the U.S., Canada, and Japan with Mutemath. “I soaked up anything I could,” says Mattison, who shared his newfound knowledge in highly educational videos such as How to Pack a Trailer. (“It’s like Jenga.”)

For years, Mattison lived primarily in a bus bunk the size of a coffin. He has some sound advice should you ever find yourself spending the night in one. “Sleep with your feet facing the front of the bus,” he says. “Otherwise, if the driver slams on the breaks, you risk breaking your neck given the forward inertia.” Noted!

Mattison’s clients have worked on albums for Kanye West, Kacey Musgraves, Chuck Berry, and more.

No One Goes into Any Creative Pursuit to Pour Over Spreadsheets

After a few years on the road with Mutemath, Mattison settled in Nashville and opened his own boutique artist management agency, Good Folk. Today, he represents five accomplished producers and songwriters: Jeremy Lutito produced Chuck, the last album by Chuck Berry. Jeremy Larson remixed “High Horse” for Kacey Musgraves. And Darren King co-wrote and co-produced “Real Friends” by Kanye West.

The more Mattison learned about the business, the more he noticed a common problem among clients: Making music is a collaboration and usually anything that you listen to is touched by multiple hands, from songwriters to producers to the band. “Real Friends” has 14 writers alone and each writer is owed a slice—”splits”—of the royalty revenue. But there is no process or tool to seamlessly divvy up song splits. Someone has to do it by hand. Others wing it. And can you really blame them?

No one goes into any creative pursuit to spend significant time each month working on spreadsheets. While the specifics of calculating splits are unique to the music community, the idea translates across all creative industries: We all spend way too much time on routine, mundane tasks that take us away from doing our most valuable work—making great stuff.

So Mattison had an idea: What if he could design a digital tool that automates this painful process and allows musicians to calculate royalty splits by simply entering their numbers and clicking a button?

It sounded simple enough, so he started designing Good Splits. He never expected that he’d soon hear from Grammy award winners, an Oscar-winning composer, even the pastor of one of the world’s largest churches. “Don’t be afraid to dismantle everything involved in your pursuit,” says Mattison.

The Good Splits UI…you can see why a calculator comes in handy.

An Endless Curiosity to Tear Things Apart to See How They Work

When Mattison designs something, he frames his approach by asking two questions: What gets in the way of creators doing their best work? And how can I remove those obstacles? “I'm a tinkerer and seeker,” he says. “I have this endless curiosity of tearing things apart to see how they work.”

Calculating song royalties, especially from digital streaming, is a huge obstacle. Every song is divided into a million little percentages based on the medium where it played, the location, and the contributors. “No one can really give you a straight answer on how music is monetized,” says Mattison.

Here’s a sense of how it works: If you’re a major artist (the people you hear on the radio), you probably hire a business manager to calculate royalty splits and pay collaborators. But if you’re a small fish (~80% of the industry), you have to pour over those unwieldy spreadsheets, spending days on something that offers little-to-no financial and creative return.

Because musicians currently can't go to an Apple Music or Spotify and put their songs directly on the streaming platforms, they have to go through a third-party distribution service. These distributors advertise they will get you on playlists, which will increase your spins, which will increase your profile, which could get you discovered. For this, distributors typically take a cut of eight to 40% of whatever your song earns online in perpetuity.

What are musicians getting for that cut? Mattison wondered. “For the distributor fees, there needs to be a service that expands the musician’s business,” he says. “Otherwise it’s a passive thing where distributors collect money from a song in perpetuity.” Mattison feels it is impossible for any service to provide more than a few months of promotion when so many songs are added online everyday. (Over 60,000 tracks are uploaded to Spotify every day. That’s nearly one per second.)

Mattison feels that trading a sizable percentage of lifetime royalties for short-term benefits doesn’t add up. “A question I always ask musicians is, ‘How much equity in your songs are you actually maintaining?’” he says. “Too often, musicians give away so much equity they feel like they make the least amount of money on something that is all theirs.”

The Good Folk logo is our spirit animal (if that can be an actual thing).

No One Will Move but Something Has to Happen

Good Splits is a free, stand-alone digital calculator that allows the individual responsible for divvying up the song’s earnings to upload their sales data, input percentage splits for each collaborator, and easily see who is owed what amount—no math required. “We ask them to bring a sales data sheet they already have, provide song splits, and hit calculate,” explains Mattison. It simplifies a complicated process and saves song owners time and headaches, while ensuring song collaborators are paid much faster than the typical six-to-nine month timeframe. “Kelly Clarkson probably isn’t going to be a user, but [smaller] artists are,” says Mattison. “This is for them.”

The royalty calculator is an alternative to distributors that take a cut of royalties. As of now, there is a single distributor, Tunecore, that charges a flat fee rather than a percentage of royalties. Mattison is pitching musicians on using Tunecore to get their songs on the streaming platforms, then using Good Splits to calculate song splits. Promote yourself through concerts. "I heard a story once about Garth's manager Bob Doyle saying if he can sell a ticket, he can sell anything," notes Mattison.

Of course, no one is selling many tickets these days—save Bow Wow—which makes Good Splits even more valuable and impactful. “When your touring revenue streams are on pause, the one thing that stays there is your streaming revenue,” says Mattison. “That has made people more aware of that money. It has always been forgotten revenue because it has been less compared to touring. But when all you have is the streaming money, you pay more attention to it.”

To date, Good Splits has facilitated nearly $1 million in royalty payments between users and saved users over 200,000 hours. The calculator has cut down Mattison’s 14-hour process each month down to six minutes. Factor that across a year, and the time saved essentially gives him 160 hours back. Now imagine that time saved at scale across every song and every play. It adds up.

Songwriters, indie musicians, management companies, and Grammy and Oscar winners have started using Good Splits. But it’s not just traditional artists. Mattison talked to a worship pastor at a mega church that releases a lot of their music. Somehow, it falls on the pastor to do pretty complex royalty accounting by hand, so Mattison set him up with Good Splits. “What used to take hours,” wrote one user, “now takes minutes.”

Don’t be Afraid to Dismantle Everything Involved in your Pursuit

To date, the middlemen distributors are not moving to get ahead of Good Splits. “It’s like that scene from The Office when they're doing the Savannah murder mystery and, at the end, they're all sitting with guns pointed at each other, but no one is shooting,” says Mattison. “It’s like that with the services. No one will move. But something has to happen.”

He recounts a conversation with his neighbors, four Belmont University students who are musicians. (Bless their heart,” he says.) The four students met with someone from a music label who said to use a certain distribution service that was...backed by that label. “I told them they had to understand that is a research and development arm for the corporation,” says Mattison. “If you run your release through that distribution service, then the corporation has immediate access into how your song is doing. That can kill or create momentum for you.”

Mattison has teamed up with digital product agency Coalesce to build Good Splits. Coalesce is also an investor in Good Splits, a bet on both the idea and on Jordan whose typically understated nature turns idealistic when asked about his end goal for Good Splits. It is for “equitable treatment of artists and creatives”, he says, though he’s starting with a more modest objective. “Right now, if we can nip crazy distribution fees in the bud that would be better for everyone.”