Take a Line for a Walk: How British Illustrator & Author Marion Deuchars Works

From her distinct hand lettering style to her award-winning illustrations, Marion Deuchars wrestles with new ways we can create our world. Portrait by Nina Tschorn; all images courtesy of Deuchars.

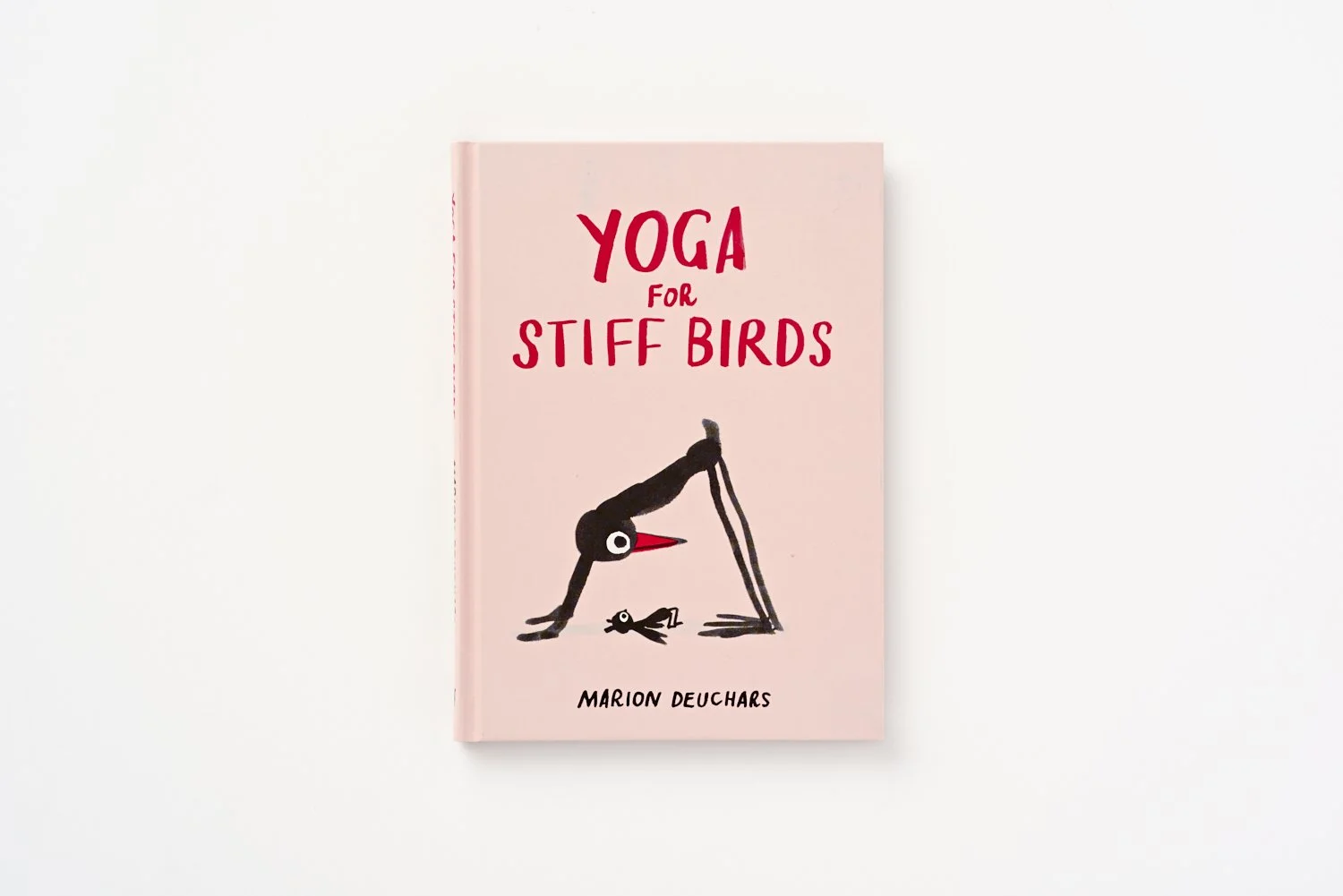

Last week, British artist and author Marion Deuchars received a note from an eighty-year-old man named Henk, thanking her for “giving him his yoga back.” He was referring to Deuchars’s illustration book, Yoga for Stiff Birds, which helps a genderless bird named Bob into every position from downward-facing dog to tree, and then encourages readers to follow suit. Since the book’s release a few years ago, the stiff bird concept has taken off. Indeed, it is as much about yoga as it is about everything else.

Born and raised in Scotland, Deuchars is a creative mastermind in every sense. Her distinct hand lettering style has appeared in numerous Jamie Oliver cookbooks, the award-winning 2009 Penguin Books cover for George Orwell’s Burmese Days, and on stamps for the Royal Mail to commemorate the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 50th anniversary. Not only that, but she has designed over 200 book covers, spent a few years at Guardian’s Saturday as the magazine’s sole illustrator, and authored numerous best-selling books, including Let’s Make Some Great Art; Make Every Day Creative; and Take a Line for a Walk, which was just released last week.

Central to her work is the idea that a little bit of creativity (or play) every day will make your life better, no matter your age or artistic abilities. Here, Deuchars shares how she works and plays, including the tasks that she gives herself on her daily walks along the London canal; creative (and literal) mess as a grounding principle in her work; and the story of why she went to Switzerland to look for her most recent book idea.

The artist at work in her London studio.

How do you spend your mornings?

Well, I am not an early riser. I know there are so many people that do the five o’clock clubs but I am a nine-hours-a-night person. When I get up, I make some breakfast and go to this great fitness club that is literally a minute away from my house. I come back for a second breakfast, read the paper (The Financial Times is given away free at the gym), and then I walk my dog to my studio.

I’m very lucky to live in London; it’s a very green city. One of my favorite walking routes is along the Regents canal to The New River Walk. It has amazing plantings with different species of trees, and you can see lots of different birds and herons there. I find those walks are kind of part of my own process. They give me a chance to think and to frame how my day is going to be.

How do you structure your workday?

I suppose I’m playing games a lot of the time. Sometimes I give myself little tasks on walks: I might tune into a sound, or look for pareidolia, which is where you find faces hidden in things like trees, sidewalks, or clouds. A lot of inspiration comes from play, and the Surrealists were kind of brilliant at it. They knew when the left side of your brain, the logical brain, gets in the way of the right side, or your creative brain, you must try to switch it off. The logical brain always wants to correct, normalize, and make things neat and safe.

If you ever watch a child drawing, it is fascinating just how absorbed they are in it; how they don’t need very much other than a piece of paper and a pencil to imagine a whole other world. Yet as adults, that zone of childlike wonder and possibility feels very far away. So I’m always trying to reach back to that space. I try to achieve that childlike state where a blank sheet of paper doesn’t make you anxious, and you can just throw yourself into any world without fear. That’s kind of the best tool ever: a crayon or pencil or pen on a piece of paper.

I start almost every project without knowing what I’m doing. I’m not someone who comes up with a great, big idea and then follows it through methodically. It’s always about, well, if I put this together and this together and then chop it up and rip it up or throw some paint on it, what is it? It’s going to give me something to start with, and from that, I will make something. I love the quote from Jasper John on making art: “Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it.”

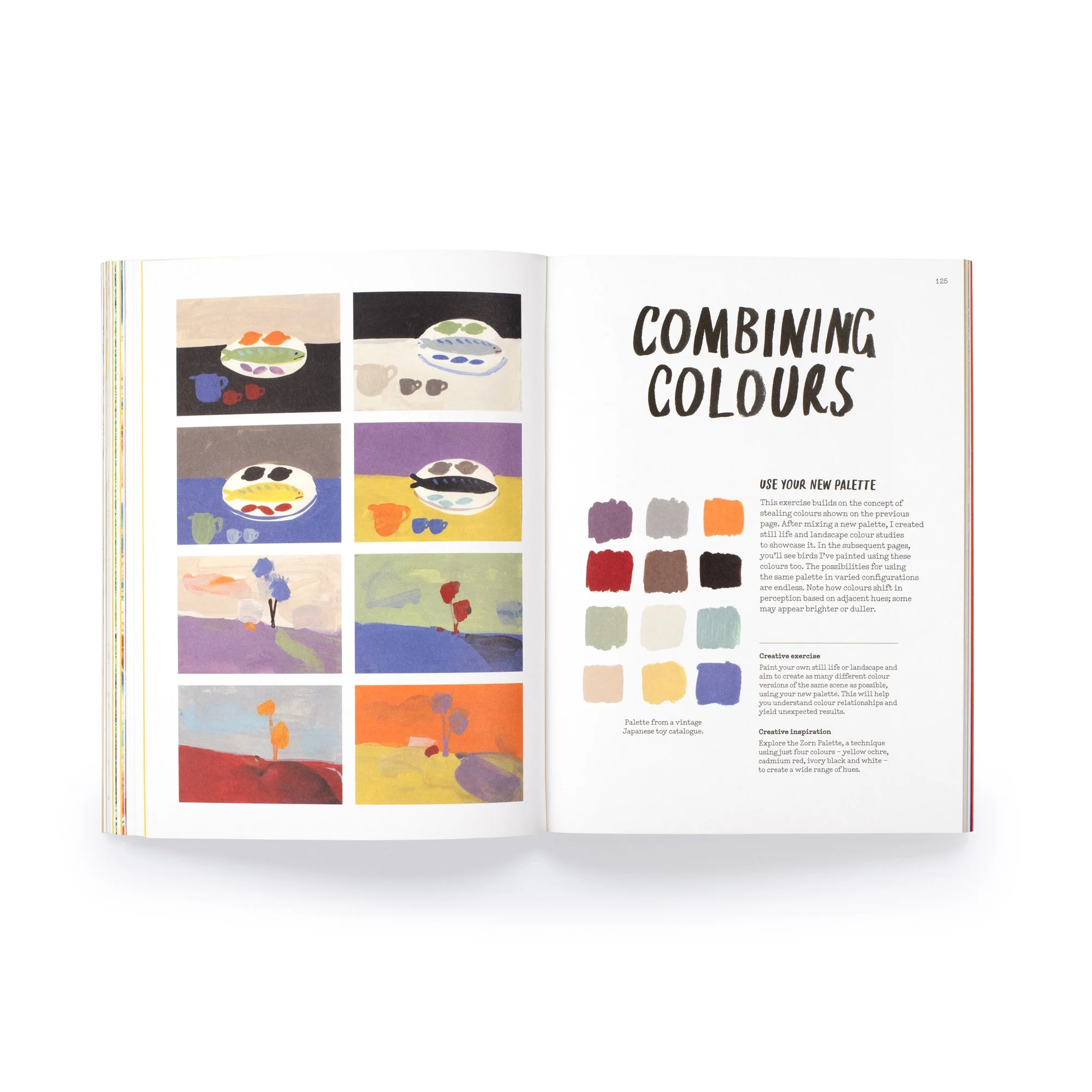

In Make Every Day Creative, Deuchars gives readers creative exercises they can use to work through any creative block.

Describe your dream studio.

I believe in the idea of a creative mess. When accidents happen in your work, it’s often a good thing. And I try to create space for that, where I can go into a childlike zone where I play and I’m not sure how things are going to turn out. For me, if everything was quite regimented and tidied in my studio, I’m not sure if I would reach that space. I wouldn’t just grab something; I wouldn’t pull some random piece of paper out. On one side of my studio is my computer, scanner, and printer for designing my books. The other area in my studio has lots of conventional art materials, like paints and papers and drawers of different bits and bobs. And my analog desk, I’d say, is where the majority of my work is made. I call it my “play desk” because most of my work is analog and experimental. In my book, Make Every Day Creative, you can see an example of my desk. It’s not super tidy; I tend to make a lot of mess and then tidy up.

Deuchars’s desk is what she calls a “creative mess.”

What’s one unique thing about your work process?

I always say that drawing is a very honest kind of translation of your thoughts; you can literally see on the page if a certain line you made was a nervous one. And I think you need to create confidence by whatever means possible, with whatever tools or methods you need to have around you. Technology has changed my working process quite a bit, in the sense that I don’t feel pressure to perfect my work on paper. The computer allows you to experiment with different elements and layouts and play around more, whereas in the past, my process was quite slow. If I made one mistake, I literally had to start over again. I used to alleviate that stress by working on doubles, or working on two different artworks at the same time. It would free me up to think, well, if I ruin that one, I’ve still got this one. So there was a kind of safety thing going on there. Now that I have digital design tools, I can put those two drawings together, and it’s brilliant, because you’re always aware that you can get something a little wrong and change it along the way.

Where do you get your ideas from?

I went to Switzerland to visit the place where Paul Klee was born because I fell in love with his work. When you get excited by something new, you follow it wherever it goes. So I went to a fantastic museum, Zentrum Paul Klee, that has a lot of his work, and it was like a kicking off point for writing my book, Take a Line for a Walk. I suppose I was trying to learn about his process and analyze some of his sketchbooks, because his work is really quite complicated. The task was trying to put that into a very simple language. He takes play to this extra level, where he’s kind of intellectualizing the play. He’ll take a round mark and turn it into a sharp mark, or he’ll be going from a warm color to a cold color, or from dark to light. Or he’s making a square, and then adding a triangle, and then adding a line and repeating that. And as I was breaking it all down, trying to understand his process, I started realizing, Well, of course, I can do that to make artwork. Suddenly there’s a whole new bunch of ideas for me to get ideas from. I got so inspired by his work that I produced a lot of work after that trip and showed it to my publisher and they said, Oh my God, we’ve got enough for two books here.

What’s one thing no one knows about your books?

The last 10 or 15% of making a book takes as long as the whole book. I’m like one of those builders that say they can fix your roof in three weeks, and then it takes three months.

Bob, the genderless stiff bird who is more than just a bird, really.

What’s the brightest idea you’ve had that has yet to see the light of day?

One of the books I’ve had in my head for some time is about Bob, the genderless bird. He’s the same character from Yoga for Stiff Birds, something I wrote because I’d started doing yoga and it was hard and it used to make me cry. I was a stiff bird. So I made an instructional book with this character as an entry-level yoga guide. The book I’m working on now is going to be called Calm for Busy Birds, and it’s about secular Buddhism and mindfulness, which is a big part of my life that I’ve never really put it into my work before. It’s quite a challenge because I’m rereading lots of things and realizing, oh, yeah, I use mindfulness a lot in my work. In fact, it’s not dissimilar to the same formula that I use to help people make art, or to help people exercise. It’s like, you have a lot of complicated information, and it’s about trying to personalize that information and make it accessible and put it out there. Of course, that book is still a big lump of play at the moment.

Join more than 50 leaders from top organizations, including Spotify, Amazon, Disney, Shake Shack, Stripe, NASA, Cannondale, Hearst, Roblox, Clay, Paramount, and Mailchimp.