Charles Brooks Finds Entire Worlds Inside Instruments

Charles Brooks uses a camera and a medical probe lens to uncover the vast interiors of instruments. Photos c/o Brooks.

Charles Brooks structures his entire day around instruments. But he doesn't just play them; he operates on them, using his camera to investigate and photograph their small, vast interiors.

The results are otherworldly. Just look at the stark interior of this Martin D35 guitar — the same type that Johnny Cash played for more than two decades. Or the first photograph ever taken inside this $20 million Stradivarius violin, where even the tiniest mistake during production could have completely destroyed it. And the interior of this rare 18th-century cello, the instrument that inspired Brooks to pursue this unconventional path.

Before turning to photography full-time, Brooks spent 20 years as a concert cellist, and in all that time, he only saw the inside of his own cello once, during major restoration work. “That brief glimpse stayed with me,” he said. “During the COVID lockdowns, I came across a medical probe lens available for hire, and the idea of putting it inside an instrument was immediate and almost instinctive.” What he did not anticipate was just how dramatic the result would be until that first shoot, when these familiar objects suddenly revealed vast, unseen worlds within them.

Here, Brooks shares the lengths he goes to in order to get these shots, including how he earns the trust of musicians to hand over their instruments, which are sometimes worth millions; why each photo depends on the perfect balance of temperature and light; and the tool he needs invented next to photograph a 9.5-foot Bösendorfer grand piano.

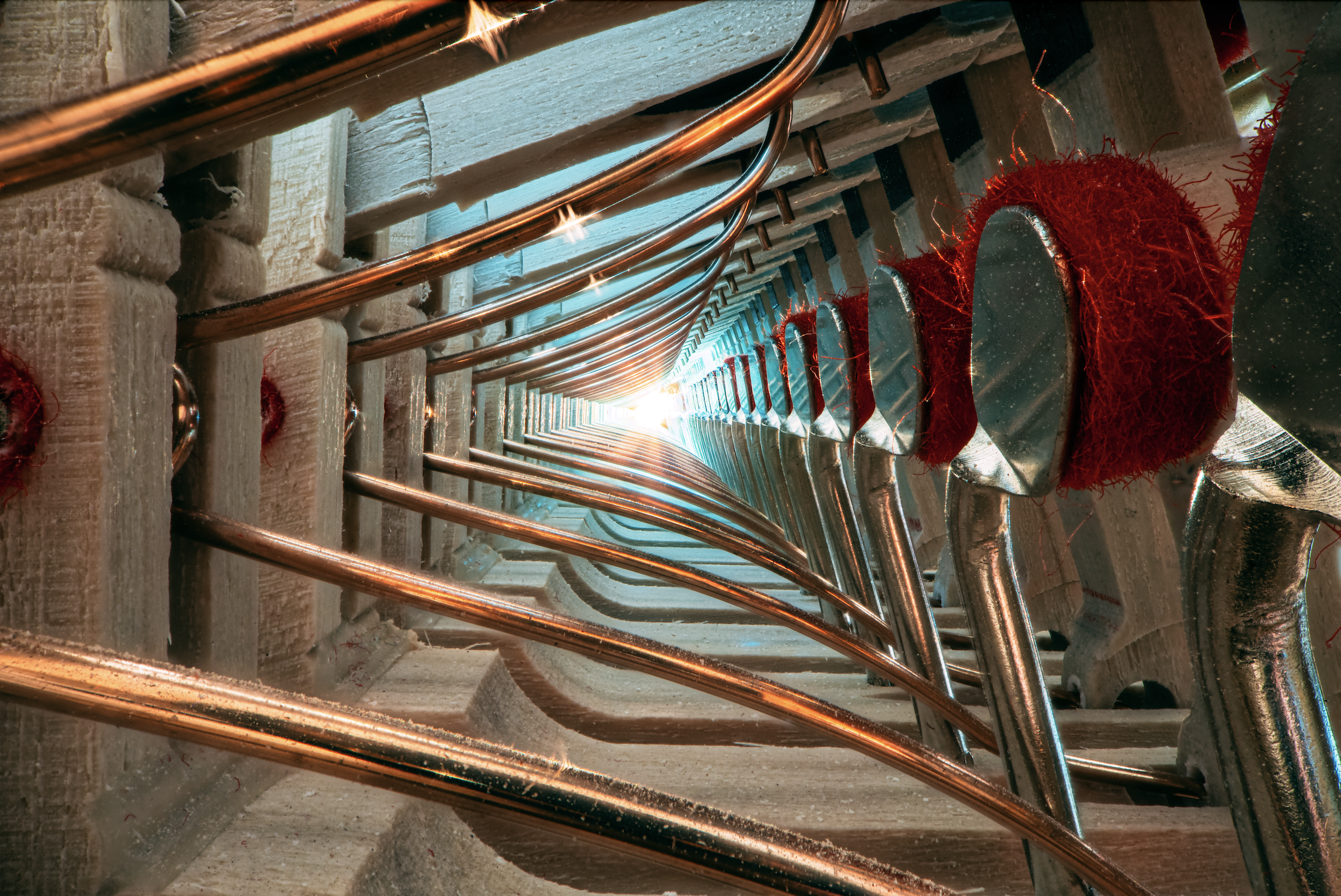

The interior of a St. Marks Pipe Organ. These are the smallest pipes in the organ, responsible for the highest notes.

What’s the craziest part of your process?

The craziest part is the level of patience and control required from start to finish. None of the images are single photographs, each one is constructed from hundreds, and often thousands, of frames captured with specially modified medical endoscopes inserted through existing maintenance openings in the instrument. These lenses are extremely dark, which means I need a lot of light, but light brings heat, so I am constantly monitoring temperature to protect instruments that can be worth tens of millions. The real work continues long after the shoot, as the images are blended to achieve full depth of field, creating an optical illusion where a space only a few centimetres wide appears vast and architectural. The process draws heavily on my background in astrophotography, with software like PixInsight used for dark frame subtraction to reduce noise, Helicon Focus for stacking, and Photoshop for final retouching, often removing dust specks that appear enormous at this scale.

How do you spend your mornings?

As a former concert cellist and now a photographer working around musicians’ schedules, my working hours often lean toward the evening. I like to sleep in when I can, but if a shoot is approaching things quickly become intense. Preparation usually starts the day before, assembling dozens of stands and lights, charging batteries, checking memory cards, and using a stand-in instrument to run test shots for light levels and heat control. This process alone can take many hours, and that’s all before the instrument even arrives.

Steinway Grand Piano.

What do you wear to work?

I keep things smart casual. The goal is to create an atmosphere where the musician feels comfortable and at ease. Many of the instruments I photograph are worth tens of millions of dollars, so there can be a lot of tension on both sides. I try to balance that by creating a space that feels calm, clean, professional, and welcoming.

How do you structure your workday?

Living in Australia means my inbox often fills up overnight. I try to ease into the day with a coffee and some news before opening work email, although more often than not the first thing I see is a flood of inquiries as I take my phone off the nightstand. My days are structured almost entirely around instrument availability. A shoot might begin at 10 a.m. or 10 p.m. and can easily run through to the early hours of the following morning.

This is the first photograph ever taken inside a Stradivarius Violin, so valuable that even the smallest crack could destroy it.

Do you have any playlist favorites?

In the days leading up to a shoot I research the specific instrument I’ll be photographing and immerse myself in recordings. Sometimes that means listening to music performed on the exact instrument, other times it’s a master of the same type. One day it might be Augustin Hadelich playing Bach and Ysaÿe on his Guarneri violin, another it could be Jacob Collier’s latest album as I prepare to photograph his guitar.

What are the tools of your trade?

I shoot exclusively on Lumix cameras. They pioneered features that are essential to my way of working, such as live view boost for extremely small apertures and pixel-shifting modes that significantly increase resolution. The most unusual tools I use, however, are medical endoscopic lenses. Made by Storz in Germany, they are normally used in surgery. I’ve had them specially adapted to work with my cameras.

Martin D35 Guitar.

Describe your dream studio.

At the moment my studio is perfectly set up for photographing the interiors of instruments. I would love to extend that to the exteriors as well, although this is far more challenging due to highly reflective surfaces. A large white-walled studio with a turntable big enough to hold a 9.5-foot Bösendorfer grand piano would be ideal. It would also need to be an enormous space.

One unique thing about your work process?

My photography involves a large number of highly technical steps borrowed from fields such as astrophotography, macrophotography, and medical imaging. Each final image combines techniques like macro focus stacking, panoramic stitching, dark frame subtraction, and many others. It’s not uncommon for a single photograph to be built from around 4,000 individual frames.

Pietro Testore Cello, late 1700s.

Do you have a mantra?

If you can imagine it, you can photograph it. If the tools don’t exist, make your own. Then have the patience to see the process through, even when it takes years.

What’s your brightest idea that has yet to see the light of day?

This one I’m keeping to myself. In keeping with my mantra, ideas I can’t yet photograph simply need more time, thought, and experimentation.

What’s a to-do list item that keeps you up at night?

When working with an extremely valuable instrument, such as a Stradivarius violin, I constantly run through the entire process in my head, anticipating anything that could go wrong so I can prevent it. The result is a kind of “Final Destination violin” movie playing on repeat, sometimes for months. It has definitely caused more than a few sleepless nights.

Join more than 75 leaders from top organizations, including Spotify, Amazon, Shake Shack, Stripe, NASA, Cannondale, Hearst, Roblox, Clay, Paramount, and Mailchimp.